what did it mean for eliezer to put a ring on rebeccas finger

The Louvre Museum, Richelieu fly, 2nd floor, room 14

Oil on canvas, 118 ten 197 cm, painted in 1648 for Pointel, a merchant from Paris whose collection primarily comprised paintings by Poussin. The canvas later became part of the collection of the Duke of Richelieu and was acquired by Louis Fourteen in 1665.

There are two other paintings by Poussin that deal with this subject, 1 of which was painted later, around 1664, possibly unfinished, and is kept at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The painting at the Louvre Museum is 1 of the almost famous, and certainly the near accomplished, works of Nicolas Poussin, forming part of the works from the period post-obit his return to Rome in 1642, a menses of 10 years during which he painted what would be considered during his time as the painter'south about perfect creations and are classed nowadays amidst the most pure expressions of French classicism.

Anthony Blunt notes that as of his return to Rome, the creative vision of Poussin underwent a revolution: he connected to piece of work with religious and classical subjects, but in both cases his involvement was displaced, particularly in terms of subjects from the Old Testament: he abandoned the spectacular accounts of the Book of Exodus and defended himself to subjects that lent themselves to dramatical or psychological estimation, such as that of Eliezer and Rebecca.

To shed lite on this subject, information technology is useful to notation the positioning of the painting in room xiv, opposite "les Israélites recueillant la manne dans le désert" ("the Israelites gathering the manna in the desert"), a canvas of similar dimensions (149 x 200 cm), which was completed in 1639, i.e. before his stay in Paris, the subject of which was taken from the Book of Exodus (Ex 16, xiii). When we compare these two works, nosotros get the feeling that the paining with the "Manna" is the opposite of the setting of "fifty'agréable tableau" ("the pleasant painting") spoken of past Félibien, the writer of one of the biographies on Poussin, with its sombre tones and vexed attitudes in a more austere setting and without architecture.

Theme of the painting: the mysteries of Grace

This painting seems to be a piece of relaxation for Poussin as he painted it following the second series of the Seven Sacraments, which is relatively austere and was dedicated to his friend and patron Paul Fréart de Chantelou and painted between 1644 and 1648.

Pointel, subsequently having admired the painting of Guido Reni, "La Vierge cousant avec ses compagnes" ("The Virgin sewing with her companions"), asked his favourite artist for a painting which, like the latter, would portray "several women, in which yous tin meet different beauties".

It was therefore not a question of parting from a specific subject, with the client reserving the right to impose restrictions on Poussin. The latter chose the biblical episode of the meeting betwixt Eliezer and Rebecca at the well of Nahor (Genesis 24): Abraham asks his old intendant, Eliezer, to go to Mesopotamia to cull a wife for his son Isaac. Arriving near a well with his ten camels, he finds – amongst the women coming to draw h2o – Rebecca, who is "very pleasant to look at" and gives water to him and his camels. Eliezer, seeing a sign of Yahweh, gives Rebecca a gilt ring and ii bracelets.

In a typological biblical approach (notice the instances of foreshadowing of the Gospels in the Former Attestation), this scene is foreshadowed in the Christian tradition of the Declaration (celebrated on 25 March). We find it in the Gospel of Saint Luke (1, 26-38), when the Archangel Gabriel announces to Mary that she is going to bring a child into the world, Jesus.

Poussin recreates this scene which – bated from the solemnity of the biblical option – does not present any event, by means of twelve immature women in the shape of statues around the two protagonists, each with a unlike attitude, confronting a landscape adorned with architecture and eliminating the "bizarre objects" that are the camels (which was at the center of a famous controversy xx years afterwards, in 1668, between Charles Le Brun and Philippe de Champaigne).

In reality, the faces of Rebecca and her twelve companions, with varied expressions, are a pretext for Poussin analysing the reactions provoked past the divine ballot: curiosity or emotion, confusion or jealousy.

The format of the painting

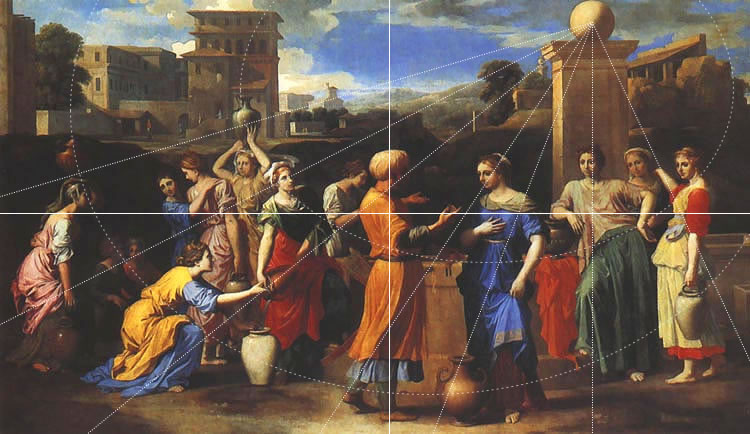

Pointel's wish, a painting bringing together dissimilar beauties, was met: the piece of work appears every bit a harmonious group of 14 chief figures enclosed in a mural adorned with architecture. This group forms a frieze, stretching from 1 office of the painting to the other, dominated by curves which dissimilarity with the compages and the different perspective angles which, by means of a network of orthogonals, recall the rectangular format of the work.

The framing

The scene unfolds correct in front of the eyes of the viewer, occupying the lower two thirds of the painting; the group of people is represented on an equal ground and none are cutting off by the edges of the piece of work: Poussin prompts us to view the scene overall, in a frontal, very accessible manner, even though certain young women, farther abroad, are partially hidden by companions which are closer to the viewer. The just thing extending beyond this frieze is the jug of the young woman looking at the viewer, as well highlighted by the intersection of the lines of the thirds (run across below).

Eliezer is at the centre of the work: the raised index finger on his correct hand is exactly at mid-summit, whilst the vertical separating the painting in two passes through the middle of his right leg, his body, his right shoulder and the eye of his turban, i.east. his caput.

The composition

Each figure seems to have its place: calculated, distant and notwithstanding close to its neighbour. Rhythm is added to the scene by numerous insistent verticals, of which the tempo, gear up by the unlike jugs, may appear sometimes fatigued-out, sometimes more hurried.

• The rule of 3 thirds

The awarding of this dominion, which is found nowadays within the context of photography, helps place the elements of the composition and brings dynamism to the work.

As stated, the scene occupies the ii lower thirds of the painting. The intersection of the lines of the thirds neatly places the accent on the grouping of five women to the left of Eliezer – notably the 1 carrying the jug and fixing the viewer's gaze – as well as on Rebecca, as a counter-point.

• The directing lines

The statuesque bodies, the necks, the heads, the eyes, the earth of rock situated on the heavy square column, and even Eliezer's turban, define a universe subjected to the laws of the sphere and the cylinder, and the architecture and different perspective angles come to enclose the round forms in a network of orthogonals, knowing that the geometric network volition ensure the triumph of reason.

• The truncated column with the globe on height

The directing lines of the work all seem to originate from the sphere situated on the truncated column, which, first of all, catches the viewer'south attention; very of import and very curious: what does it hateful? Why did Poussin permit the intrusion of this abstract element that, in theory, doesn't stand for to anything in the painting's infinite?

According to Milovan Stanic, it is about the joining of Virtue (represented past the square base) and Fortune (Fortuna in Latin, a Roman goddess who distributes her blessings haphazardly), one of the primary attributes of which is the globe.

The well, location of choice for mystical weddings, locus fortunae, is marked by this emblem, which serves as the condensed commentary of the scene.

Rebecca, who meets her destiny earlier this well, also has a first name which means "patience", a distinguished virtue.

Milovan Stanic also reminds us that the architectural emblem of Virtus and Fortuna is ane of those favoured by Alberti (Leon Battista, 1404-1472): "a humanist emblem par excellence, combining human being action into the earth with moral ends"; and we know that, co-ordinate to Poussin, the real subject of painting is the actions of man.

In this way, this curious element of architecture is seen every bit representing the eternal presence of divine providence.

As a concluding note: the artist has mirrored this with a like architectural chemical element, only to the left and behind.

The symbolic function of the jugs

The author has given rhythm to the directing lines by way of an interplay of jugs (at to the lowest degree 10) as if he was playing with the formal motif of the jug: here nosotros can run across vases, with forms shut to that of the amphora, the pelike and the Greek stamnos or hydria.

The parallel with feminine forms is inescapable. In arriving at the well, Eliezer is interfering in a feminine world. Nosotros now sympathize why the painter did not want to include the bizarre and anaesthetic forms of the camels.

We can therefore reconcile the vase, the jug, with the idea of virginity: Is Poussin peradventure emphasising the innocence or purity of Rebecca?

Finally, nosotros can once more find the theme of divine election and salvation in the water, which is omnipresent hither and evokes the idea of baptism.

Beneath are the details of the work:

Source: https://www.nicolas-poussin.com/en/works/eliezer-and-rebecca/

0 Response to "what did it mean for eliezer to put a ring on rebeccas finger"

Post a Comment